You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Metropolitan Opera’ tag.

The advance notice for the November 9, 1891, performance of Lohengrin included the names of producers, principal singers, conductor, and stage manager, but not the accompanying orchestra.

Following the third subscription week of its first season, the Chicago Orchestra was in the pit of the Auditorium Theatre for performances by the Metropolitan Opera Company from November 9 until December 12, 1891, including three run-out performances at the Amphitheatre Auditorium in Louisville, Kentucky, on December 7 and 8.

The first opera given was Wagner’s Lohengrin—sung in Italian—led by Auguste Vianesi, the Orchestra’s first guest conductor. That performance featured no less than five singers making their U.S. debuts: soprano Emma Eames, mezzo-soprano Giulia Ravogli, baritone Antonio Magini-Coletti, and tenor and bass brothers Jean and Édouard de Reszke.

On November 10, 1891, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that even though several patrons were late in arriving due to “the fact that carriages approached in single file and the process of unloading was rather slow . . . [they] failed to dismay Sig. Vianesi, who began his calisthenic exercise with the baton promptly at eight. Eighty-five musicians of the Chicago Orchestra played the graceful Lohengrin prelude in a style which in the show-bill style was ‘alone worth the price of admission.’”

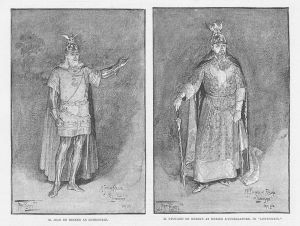

Wood engraved print by Fred Pegram of Jean and Edouard de Reszke—as Lohengrin and Heinrich—from The Illustrated London News in 1891

In the title role, Jean de Reszke “has the dignity and aplomb of an artist to the manner born and the glittering armor of the Knight of the Grail becomes him well. . . . [He] is an artist to the tips of his mailed boots and gloves. He has immense personal magnetism, and when he casually conveyed to Elsa the information, ‘Io t’amo,’ there was a responsive thrill under many a pretty corsage bouquet.”

“Her voice is one of beauty, and she uses it in a manner that shows great care and study in the training of it,” continued the reviewer in describing Emma Eames. “Here is a classic beauty, and a more charming picture than she presented when clothed in the wedding robes of Elsa has rarely been seen upon any stage.”

On November 14, the New York Times reported from Chicago. “It was though reason for not a little regret both in New York and this city when it was announced that the management of the Metropolitan Opera House, which in a measure seems to control the operatic destiny of the country, had decided to discontinue German opera this year and to substitute therefore Italian opera. By selecting Lohengrin as the opera with which to open the present season, Messrs. Abbey and Grau made a praiseworthy compromise. All fears that the season would be composed of a series of repetitious of hackneyed Italian operas were thus allayed. It is too early to pass any judgment, but, according to the indications to be found in this week’s performances, it is almost safe to assume that in many respects this year will witness some of the most brilliant performances of grand opera ever given in this country.”

Regarding Édouard de Reszke as Heinrich, the Times continued, that he was “endowed with a voice which for power and quality, richness and warmth, range and volume, has seldom been equaled. He displayed the highest art in the use of it. His acting also was artistic, and dignified, and his impersonation was in every respect a regal one.” As Ortrud, Giulia Ravogli, “displayed histrionic ability of an exceptionally high order and a mezzo-soprano voice of extensive compass and considerable power.”

Additional singers who appeared during the residency were among the most famous of the day, including sopranos Emma Albani, Lilli Lehmann and Marie Van Zandt; mezzo-soprano Sofia Scalchi; tenor Fernando Valero; baritones Edoardo Camera and Jean Martapoura; and bass Jules Vinché. A staggering number of operas were performed, including Bellini’s Norma and La sonnambula; Flotow’s Martha; Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice; Gounod’s Faust and Romeo and Juliet; Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana; Meyerbeer’s Dinorah and Les Huguenots; Mozart’s Don Giovanni; Thomas’s Mignon; and Verdi’s Aida, Otello and Rigoletto.

The final offering of the month-long residency on December 12 was a fourth performance of Lohengrin, and changes in the cast included Valero in the title role, Albani as Elsa, and Vinché as Heinrich; Louis Saar conducted. Two days later on December 14, the company was back in New York for the Metropolitan Opera’s season opening: Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet featuring Eames and the de Reske brothers with Vianesi on the podium.

After two run-out performances on December 15 (at the Odeon in Cincinnati) and 16 (in Indianapolis), founder and first music director Theodore Thomas and his Chicago Orchestra resumed the regular season with the fourth subscription week at the Auditorium on December 18.

Susanna Mälkki leads the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Wagner’s Prelude to Lohengrin on March 21, 23, and 24, 2024.

This article also appears here, and an abbreviated version appears in the program book.

Amelia Earhart standing under the nose of her Lockheed Model 10-E Electra on March 1, 1937 (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

On May 20 and 21, 1932, American aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart flew a Lockheed Vega 5B from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, to Culmore in Northern Ireland, becoming the first woman (and the second person) to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Less than three years later on January 11 and 12, 1935*, she became the first aviator to fly solo from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California. After a little more than a month, she was in Chicago and presented a lecture on February 15 at Orchestra Hall entitled, “My Pacific Flight.”

“Women fliers have a definite place in the air transport service as pilots, Amelia Earhart, America’s first lady of the air, declared yesterday as she arrived in Chicago, her old home town,” William Westlake reported in the Herald & Examiner. “The arrival of the smiling modishly-attired former Hyde Park High School girl [she graduated in 1916], who has twice flown the Atlantic and made a solo flight from Honolulu to Oakland, was without fanfare. . . . Tonight she speaks again at the South Shore Country Club, tomorrow night she talks at the LaGrange Sunday Evening Club, and then she is off to Kansas City and Omaha.”

In the Chicago Tribune, Wayne Thomis reported that the Orchestra Hall audience, comprised largely of women, heard Earhart speak, “deprecatingly of her flight’s value as an advancement for aviation. . . . Although Miss Earhart spoke appreciatively of a few grim moments when she took off with a heavy load of gasoline downwind from a muddy field on her Pacific flight, it was the lighter side of ‘my pleasant evening in the air’ that she stressed. There was a bit of pride, too, in her reference to the fact that she had flown exactly on her course throughout the 2,038-mile voyage although she made the flight by dead reckoning. Soon after leaving the islands behind, the commercial program broadcast from a Honolulu radio station on which she was tuned was interrupted, she said. ‘I was listening to the music and then the announcer said: “Miss Earhart has taken off on her flight to San Francisco.” And as I sat up there at 8,000 feet with the motor just in front of me, I thought: “How impertinent of that radio man to be telling me.” ’ “

On May 21, 1937, Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan left Oakland, California, traveling east in a twin-engine Lockheed Model 10-E Electra, beginning an around-the-world flight. Departing Miami, Florida, on June 1, they reached Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, having covered 22,000 miles. On July 2, they left Lae for their next refueling stop, Howland Island; however, they were soon reported missing over the Central Pacific Ocean. A large-scale sea and air search was launched, and by July 18, they were declared lost at sea.

“The most recent group to join the search—a team of underwater archaeologists and marine robotics experts with Deep Sea Vision, an ocean exploration company based in Charleston, South Carolina—says it may have found a clue that could bring some closure to Earhart’s story,” according to recent reporting by . “By using sonar imaging, a tool for mapping the ocean floor that uses sound waves to measure the distance from the seabed to the surface, the group has spotted an anomaly in the Pacific Ocean—more than 16,000 feet (4,877 meters) underwater—that resembles a small aircraft. The team believes that anomaly could be a Lockheed 10-E Electra, the ten-passenger plane that Earhart was piloting when she went missing while attempting to fly around the world. . . . [DSV] hopes to return to the site within the year to get further confirmation that the anomaly is a plane, which would most likely involve the use of an ROV (remotely operated vehicle) with a camera that would allow the object to be investigated more closely. The team would also look into the possibility of bringing their find to the surface.” The mystery continues.

*According to Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon’s 1997 book Amelia: The Centennial Biography of an Aviation Pioneer, Earhart enjoyed listening to the radio while flying, including “the broadcast of the Metropolitan Opera from New York.” The Met’s performance history database indicates the Saturday, January 12, 1935, broadcast as Wagner’s Tannhäuser featuring Lauritz Melchior, Maria Müller, Dorothee Manski, Richard Bonelli, and Ludwig Hofmann. Artur Bodanzky conducted.

This article also appears here.

In February 2022, we celebrate the 125th anniversary of the birth of the great American contralto Marian Anderson. She was born in Philadelphia on February 27, 1897, and died in Portland, Oregon, on April 8, 1993, at the age of 96.

On November 18, 1929, Marian Anderson (under the management of Arthur Judson) made her debut in Orchestra Hall under the auspices of the Theta Omega chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. That evening, Anderson “reached near perfection in every requirement of vocal art,” wrote Herman Devries in the Chicago Evening American. “The tone was of superb timbre, the phrasing of utmost refinement, the style pure, discreet, musicianly . . . a talent still unripe, but certainly a talent of potential growth.” In attendance were Ray Field and George Arthur, representatives from the Rosenwald Fund, who encouraged her to apply for a fellowship to further her studies in Europe. The following year, she received $1,500 to study in Berlin.

In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution refused Anderson the opportunity to give a concert for an integrated audience in Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall. With the support of President Franklin D. and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, she instead performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, to a crowd of 75,000 people and over a million radio listeners. Anderson closed the recital with the spiritual “My soul is anchored in the Lord” in an arrangement by Florence Price.

A few weeks later, on May 20, 1939, Anderson was scheduled to make her debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at the North Shore Music Festival, in Evanston’s Dyche Stadium (now Ryan Field). The afternoon program was to include arias from Donizetti’s La favorita and Debussy’s L’enfant prodigue, along with spirituals, all under the baton of Frederick Stock. A case of laryngitis, however, prevented her from performing, and soprano Kirsten Flagstad, scheduled for the evening concert, was asked to fill in for the matinee. According to the Chicago Daily News, there was no time for Flagstad to rehearse the extra program with the Orchestra due to “a purely feminine” hesitation: she needed a different dress for the matinee. Festival organizers quickly took her to Marshall Field’s to shop for a second dress, and the concert, featuring several excerpts from Wagner’s operas, was “amply redeemed by the artistry of Mme. Flagstad,” according to Janet Gunn in the Chicago Herald and Examiner.

Her debut performance with the CSO was at a concert opening the 48th Convention of the American Federation of Musicians on June 5, 1944, at the Stevens Hotel (now the Hilton Chicago). Under third music director Désiré Defauw, she sang “O mio Fernando” from Donizetti’s La favorita, “Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix” from Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah, and spirituals.

Anderson broke barriers on January 7, 1955, when she made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera—in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera as Ulrica—becoming the first African American to sing with the company. The following year, she opened the Ravinia Festival’s 21st season, along with the CSO under Eugene Ormandy in two programs, performing the following:

June 26, 1956

BRAHMS Dein blaues Auge, Op. 59, No. 8

BRAHMS Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer, Op. 105, No. 2

BRAHMS Der Schmied, Op. 19, No. 4

BRAHMS Von ewiger Liebe, Op. 43, No. 1

BRAHMS Alto Rhapsody, Op. 53 (with the Swedish Glee Club; Harry T. Carlson, director)

June 28, 1956

BIZET Agnus Dei

BIZET Ouvre ton coeur

SAINT-SAËNS Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix from Samson and Delilah

TCHAIKOVSKY None but the Lonely Heart, Op. 6, No. 6

TRADITIONAL IRISH Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms

KREISLER The Old Refrain

According to Seymour Raven in the Chicago Tribune, a crowd of more than 4,000 attended the all-Brahms concert that “turned out to be perfect.” Anderson sang “introspectively and with tender regard [and] exceptional craftsmanship and feeling.”

On August 28, 1963, Anderson performed “He’s got the whole world in his hands” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

During the 1964-65 season, Anderson gave a farewell recital tour under the auspices of her longtime presenter, Sol Hurok. Her stop in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall on Dec. 6, 1964, was sold out (an additional 225 seats were onstage) and “well-wishers had also provided a red carpet, bouquets of red roses and white carnations by the armload,” according to the Chicago Tribune. “This is probably no time for sentiment,” Anderson commented. “But do let me say I find all of this today very touching.” Her encores included “There’s no hiding place down there” and Schubert’s “Ave Maria.”

On June 27, 1968, at Ravinia, Anderson made her final appearance with the CSO, as narrator in Copland’s Preamble for a Solemn Occasion. Festival music director Seiji Ozawa conducted. Reading the “stirring segment from the United Nations charter,” wrote Thomas Willis in the Chicago Tribune, Anderson was “radiant in a cherry red velvet cape [contributing] both the presence and conviction, which made her vocal performances such moving experiences.”

Anderson gave a total of 22 recitals in Orchestra Hall, as follows:

November 18, 1929

January 26, 1931

October 28, 1945

November 3, 1946

November 23, 1947

October 24, 1948

January 21, 1950

January 29, 1950

January 21, 1951

April 8, 1951

May 3, 1952

January 31, 1953

March 29, 1953

January 30, 1954

December 5, 1954

January 8, 1956

February 23, 1957

April 5, 1959

February 28, 1960

February 19, 1961

May 11, 1963

December 6, 1964

In September 2021, Sony Classical released Marian Anderson: Beyond the Music, a special fifteen-CD set of recordings representing her complete catalog on RCA Victor, from her debut in 1924 through her final LP in 1966. The set received a 2022 Grammy Award nomination for Best Historical Album.

Special thanks to Eva Wilhelm—a music business student at Indiana State University and an intern in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association’s Rosenthal Archives—for her exceptional research in preparing this article.

This article also appears here.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra family mourns the loss of Clarendon Van Norman, former principal horn, who died on Sunday, April 18, 2021, at home in Monroe Township, New Jersey. He was ninety.

Born in Galesburg, Illinois, on August 23, 1930, Van Norman attended Galesburg High School, and after graduating in 1948, he began studies at the Juilliard School in New York City. After serving as a sergeant in the Airmen of Note in the United States Air Force during the Korean War from 1950 to 1954, he graduated from Juilliard in 1957. Van Norman also earned a doctorate in education from Columbia University, graduating in 1965.

Van Norman served as principal horn in the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra for two seasons before seventh music director Jean Martinon invited him to the same position in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, beginning in the fall of 1963. After serving for two seasons, he joined the orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, performing as co-principal horn and third horn until his retirement in 1990.

In his retirement, Van Norman was a member of the Long Island Antiquarian Book Dealers Association, Rotary International, and the First Presbyterian Church in Levittown, New York, where he helped with various church committees. He also was an antiquarian book dealer, taught in his private horn studio, and was a member of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Alumni Association.

Clarendon Van Norman is survived by his wife of forty-three years, Linda Van Norman, along with his two sons, Mark (Shenan) and Thomas (Kali), daughter May (Terrence) Van Norman, and sister Marilyn Van Norman, as well as six grandchildren and twelve great-grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his daughter Diane and son Steven Emery. Services will be private.

Advertisement for Verdi’s Aida with the Metropolitan Opera and the (uncredited) Chicago Orchestra on December 10, 1891 (image courtesy of the Newberry Library)

Less than a month after its inaugural concerts in October 1891, the Chicago Orchestra was in the pit at the Auditorium Theatre for performances with the Metropolitan Opera Company (under the auspices of Abbey, Schoeffel, and Grau).

The singers who appeared were among the most famous of the day, including sopranos Emma Albani, Lilli Lehmann, and Marie Van Zandt and mezzo-sopranos Sofia Scalchi and Giulia Ravogli. During the residency, other prominent singers made their U.S. debuts, including soprano Emma Eames; tenor Jean de Reszke; baritones Edoardo Camera, Antonio Magini-Coletti, and Jean Martapoura; and basses Édouard de Reszke and Jules Vinche. Conducting duties were shared by Auguste Vianesi and Louis Saar, the Orchestra’s first guest conductors.

Opening with Wagner’s Lohengrin on November 9, the residency continued through December 12 and included a staggering number of operas: Bellini’s Norma and La sonnambula; Flotow’s Martha; Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice; Gounod’s Faust and Romeo and Juliet; Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana; Meyerbeer’s Dinorah and Les Huguenots; Mozart’s Don Giovanni; Thomas’s Mignon; as well as Verdi’s Rigoletto and act 1 of La traviata.

The residency also included a single performance of Verdi’s Aida on December 10 with Lehmann in the title role, de Reszke as Radamès, Ravogli as Amneris, Magini-Coletti as Amonasro, Enrico Serbolini as Ramfis, Lodovico Viviani as the King, and M. Grossi as the Messenger. The Metropolitan Opera Chorus was prepared by its director, Carlo Corsi, and Louis Saar conducted.

“Jean de Reszke and Lilli Lehmann bade farewell to Chicago last evening by appearing together in Verdi’s Aida,” wrote the reviewer in the Chicago Tribune. “It was a performance which for superb solo work, excellence of ensemble, and splendor of scenic and spectacular effects has not been equaled in this city—a performance which marked the highest point on the standard of excellence yet reached by the Abbey-Grau company.”

German soprano Lilli Lehmann—under the guidance of Richard Wagner—created the roles of Woglinde (in Das Rheingold and Götterdämmerung), Helmwige, and the Forest Bird in the first Ring cycle during the inaugural Bayreuth Festival in 1876. She made her American debut at the Metropolitan Opera as Carmen on November 25, 1885; five days later, she sang Brünnhilde in Die Walküre and the following year Isolde in the American premiere of Tristan and Isolde. Lehmann regularly performed at the Salzburg Festival—also serving as its artistic director—and her operatic repertoire ultimately included 170 roles in 114 operas. A notable teacher, her students included Geraldine Farrar and Olive Fremstad.

“Mme. Lehmann found in Aida a role which permitted a display of her splendid histrionic gifts, and the music to which was more nearly suited to her vocal powers than has been any she has sung this engagement,” continued the Chicago Tribune reviewer. “Her success was, therefore assured and splendidly she achieved it. Her acting of the slave princess was forceful, intense, at all times free from all exaggeration or extravagance. As for her vocal work, it commands unqualified and almost unlimited praise. The ‘Ritorna vincitor’ was given with marvelous appreciation of its sad, troubled character, and the ‘Numi, pietà’ was beautiful in the purity and simplicity of its interpretation. In the long duet with Amneris in act 2, Mme. Lehmann’s singing and acting possessed great power, and in the climax at the end of the act, her voice stood out with telling effect. It was in the third act that the finest vocal work was done. Anything more satisfactory than her singing of the ‘O patria mia’ and the heavy dramatic music which follows cannot be imagined. The ‘Vedi? . . . di morte l’angelo,’ in the last scene of the opera, was exquisite in its delicacy and poetry.”

Born in Poland, Jean de Reszke began his career as a baritone in 1874, debuting in Venice as Alfonso in Donizetti’s La favorita. By 1879, he had made the switch to tenor when he sang the title role in Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable in Madrid. De Reszke was soon a regular at the Paris Opera and at London’s Covent Garden, performing the major French, Wagner, and Verdi roles; the title role in Massenet’s Le Cid—premiered in Paris in 1885—was written for him. His American debut was the opening night of the Metropolitan Opera’s residency with the Chicago Orchestra in the title role of Wagner’s Lohengrin on November 9, 1891. After his debut the following month with the company in New York—as Gounod’s Romeo on December 14—he was a regular with the Metropolitan until his retirement from the stage in 1904, settling in Poland to breed racehorses and Paris to teach singing. His students included Bidu Sayão and Maggie Teyte.

“Jean de Reszke’s triumph as Radamès was a triumph of voice and vocal art. Not that the dramatic side of the character was not developed. It was developed with the same consummate skill which has made his dramatic treatment of every role in which he has seen truly remarkable. But Radamès makes far greater demand upon a tenor’s vocal powers than upon his histrionic. Much of the music is purely lyrical in character, while other portions are strongly dramatic. A singer to do it justice must, therefore, combine the qualities of a tenore de grazia and a tenore robusto—a combination but rarely found. Jean de Reszke is such, however, and his singing of the music of Radamès is not alone satisfactory but an artistic treat of the highest kind. The famed ‘Celeste Aida’ was sung with a smoothness, clearness, and tonal beauty which were the perfection of pure vocal art, while the impassioned music of the third act was delivered with a vigor and intensity and a display of thrilling high notes which showed how dramatic singing may become and yet never cease to be singing nor degenerate into shouting.”

Portions of this article previously appeared here.

Riccardo Muti leads soloists Krassimira Stoyanova, Anita Rachvelishvili, Francesco Meli, Kiril Manolov, Ildar Abdrazakov, Eric Owens, Issachah Savage, Kimberly Gunderson, and Tasha Koontz, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (prepared by Duain Wolfe) in Verdi’s Aida on June 21, 23, and 25, 2019.

The advance notice for the November 9, 1891, performance of Lohengrin included the names of producers, principal singers, conductor, and stage manager, but not the accompanying orchestra.

Following the third subscription week of its first season, the Chicago Orchestra (as we were then known) was in the pit of the Auditorium Theatre for performances by the Metropolitan Opera Company from November 9 until December 12, 1891, including three run-out performances at the Amphitheatre Auditorium in Louisville, Kentucky on December 7 and 8.

The first opera given was Wagner’s Lohengrin—sung in Italian—led by Auguste Vianesi, the Orchestra’s first guest conductor. That performance featured no less than five singers making their U.S. debuts: soprano Emma Eames, mezzo-soprano Giulia Ravogli, baritone Antonio Magini- Coletti, and tenor and bass brothers Jean and Édouard de Reszke.

On November 10, 1891, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that even though several patrons were late in arriving due to “the fact that carriages approached in single file and the process of unloading was rather slow . . . [they] failed to dismay Sig. Vianesi, who began his calisthenic exercise with the baton promptly at eight. Eighty-five musicians of the Chicago Orchestra played the graceful Lohengrin prelude in a style which in the show-bill style was ‘alone worth the price of admission.’”

Wood engraved print by Fred Pegram of Jean and Edouard de Reszke—as Lohengrin and Heinrich—from The Illustrated London News in 1891

In the title role, Jean de Reszke “has the dignity and aplomb of an artist to the manner born and the glittering armor of the Knight of the Grail becomes him well. . . . [He] is an artist to the tips of his mailed boots and gloves. He has immense personal magnetism, and when he casually conveyed to Elsa the information, ‘Io t’amo,’ there was a responsive thrill under many a pretty corsage bouquet.”

On November 14, The New York Times reported from Chicago. “It was though reason for not a little regret both in New York and this city when it was announced that the management of the Metropolitan Opera House, which in a measure seems to control the operatic destiny of the country, had decided to discontinue German opera this year and to substitute therefore Italian opera. By selecting Lohengrin as the opera with which to open the present season, Messrs. Abbey and Grau made a praiseworthy compromise. All fears that the season would be composed of a series of repetitious of hackneyed Italian operas were thus allayed. It is too early to pass any judgment, but, according to the indications to be found in this week’s performances, it is almost safe to assume that in many respects this year will witness some of the most brilliant performances of grand opera ever given in this country.”

Regarding Édouard de Reszke as Heinrich, the Times continued, that he was “endowed with a voice which for power and quality, richness and warmth, range and volume, has seldom been equaled. He displayed the highest art in the use of it. His acting also was artistic, and dignified, and his impersonation was in every respect a regal one.” As Ortrud, Giulia Ravogli, “displayed histrionic ability of an exceptionally high order and a mezzo-soprano voice of extensive compass and considerable power.”

Additional singers who appeared during the residency were among the most famous of the day, including sopranos Emma Albani, Lilli Lehmann, and Marie Van Zandt; mezzo-soprano Sofia Scalchi; tenor Fernando Valero; baritones Edoardo Camera and Jean Martapoura; and bass Jules Vinché. A staggering number of operas were performed, including Bellini’s Norma and La sonnambula; Flotow’s Martha; Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice; Gounod’s Faust and Romeo and Juliet; Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana; Meyerbeer’s Dinorah and Les Huguenots; Mozart’s Don Giovanni; Thomas’s Mignon; and Verdi’s Aida, Otello, and Rigoletto.

The final offering of the residency on December 12 was a fourth performance of Lohengrin, and changes in the cast included Valero in the title role, Albani as Elsa, and Vinché as Heinrich; Louis Saar conducted. Two days later on December 14, the company was back in New York for the Metropolitan Opera’s season opening: Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet featuring Eames and the de Reske brothers with Vianesi on the podium.

After two run-out performances on December 15 (at the Odeon in Cincinnati) and 16 (in Indianapolis), founder and first music director Theodore Thomas and his Chicago Orchestra resumed the regular season with the fourth subscription week at the Auditorium on December 18.

An abbreviated version of this article appears in the program book for the December 14, 15, 16, and 19, 2017, CSO concerts led by Jaap van Zweden. Special thanks to our colleagues at the Metropolitan Opera and their performance history database.

Amelia Earhart standing under the nose of her Lockheed Model 10E Electra on March 1, 1937 (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

On May 20 and 21, 1932, Amelia Earhart flew a Lockheed Vega 5B from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, to Culmore in Northern Ireland, becoming the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. On January 11 and 12, 1935, she became the first aviator to fly solo from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California. And on July 2, 1937, Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan were reported missing over the Central Pacific Ocean during their attempt to fly around the globe.

Newly rediscovered image of what may be Noonan and Earhart on a dock in the Marshall Islands (National Archives photo)

However, a photographic image—recently rediscovered in the National Archives—may dispute that long-held belief. According to Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence, produced by HISTORY, this image may prove that Earhart and Noonan actually survived. The program airs this Sunday, July 9; to watch a preview and read more, click here.

A little more than a month after Earhart’s January 1935 solo flight, she was in Chicago and presented a lecture on February 15 at Orchestra Hall entitled, “My Pacific Flight.”

“Women fliers have a definite place in the air transport service as pilots, Amelia Earhart, America’s first lady of the air, declared yesterday as she arrived in Chicago, her old home town,” William Westlake reported in the Herald & Examiner. “The arrival of the smiling modishly-attired former Hyde Park High School girl, who has twice flown the Atlantic and made a solo flight from Honolulu to Oakland, was without fanfare. . . . Tonight she speaks again at the South Shore Country Club, tomorrow night she talks at the LaGrange Sunday Evening Club, and then she is off to Kansas City and Omaha.”

In the Chicago Tribune, Wayne Thomis reported that the Orchestra Hall audience, comprised largely of women, heard Earhart speak, “deprecatingly of her flight’s value as an advancement for aviation. . . . Although Miss Earhart spoke appreciatively of a few grim moments when she took off with a heavy load of gasoline downwind from a muddy field on her Pacific flight, it was the lighter side of ‘my pleasant evening in the air’ that she stressed. There was a bit of pride, too, in her reference to the fact that she had flown exactly on her course throughout the 2,038-mile voyage although she made the flight by dead reckoning. Soon after leaving the islands behind, the commercial program broadcast from a Honolulu radio station on which she was tuned was interrupted, she said. ‘I was listening to the music and then the announcer said: “Miss Earhart has taken off on her flight to San Francisco.” And as I sat up there at 8,000 feet with the motor just in front of me, I thought: “How impertinent of that radio man to be telling me.” ’ ”

(According to Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon’s 1997 book Amelia: The Centennial Biography of an Aviation Pioneer, some of the music Earhart enjoyed included “the broadcast of the Metropolitan Opera from New York.” The Met’s performance history database indicates the Saturday, January 12, 1935, broadcast as Wagner’s Tannhäuser featuring Lauritz Melchior, Maria Müller, Dorothee Manski, Richard Bonelli, and Ludwig Hofmann. Artur Bodanzky conducted.)