You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Charles A. Knorr’ tag.

The Chicago Orchestra first performed Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah on March 13 and 14, 1893, at the Auditorium Theatre in collaboration with the Apollo Musical Club. William L. Tomlins, the Apollo’s long-serving director, was on the podium. “The performance yesterday o’ertopped all previous ones in merit and has place among the finest efforts of the society,” wrote a critic in the Chicago Tribune. “The chorus was present in full working strength, the voices were clear and sure, and leader and singers entered into their work with spirit and confidence, the result being a rendition of the choral portions of the oratorio that was eminently satisfactory.”

The principal soloists on hand were some of the preeminent international singers of the day, including soprano Lillian Nordica, contralto Christine Nielson-Dreier, tenor Italo Campanini, and bass-baritone Plunket Greene.

American Lillian Nordica (1857–1914) was one of the foremost dramatic sopranos of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Following studies at the New England Conservatory, she established her career in Europe, before making her American opera debut in New York on November 26, 1883 as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust with Mapleson’s company at the Academy of Music. She performed at Covent Garden and the Bayreuth Festival and was a stalwart with the Metropolitan Opera in New York for nearly two decades. A noted supporter of equal rights for women, Nordica frequently spoke out on the pay disparity between men and women singers. Using her celebrity status, she was a staunch advocate for the women’s suffrage movement, giving concerts, donating funds, and regularly speaking publicly and in the press.

Her performance in Elijah was her debut with the Chicago Orchestra, and she sang “with the dramatic feeling and the brilliancy it demands.” Nordica later appeared with the Orchestra on numerous occasions, on subscription concerts at the Auditorium Theatre, at the World’s Columbian Exposition, and as a leading artist with the Metropolitan Opera on tour.

Originally from Madison, Wisconsin, contralto Christine Nielson-Dreier (1866–1926) gained initial acclaim during her first tour of Europe in 1889, especially at the Palais du Trocadéro during the Exposition Universelle in Paris. The following year, she performed at the concert dedicating the grand organ at the Auditorium Theatre. During the first week of the Chicago Orchestra’s inaugural season, she was soloist with the ensemble and Theodore Thomas on the first run-out concert to to Rockford, Illinois, on October 18, 1891. Nielson-Dreier later appeared with the Orchestra at the World’s Columbian Exposition and on subscription concerts at the Auditorium, and she also was soloist at Fourth Presbyterian Church for many years. In Elijah, her performance was noted as a “pleasant feature of the evening. She sings with taste, intelligence, and skill,” delivering her “finest work” in the aria “O Rest in the Lord.”

Italian tenor Italo Campanini (1845–1896) established his career primarily in London before becoming the first leading tenor at the Metropolitan Opera. He inaugurated the company’s new house on October 22, 1883, in the title role in Gounod’s Faust with Christine Nilsson (not to be confused with Christine Nielson-Dreier) as Marguerite. Campanini had previously appeared with the Chicago Orchestra on subscription concerts as well as the ensemble’s first performances of Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust during the inaugural season.

(Italo’s brother and conductor Cleofante Campanini made his debut in this country in New York in 1888, leading the U.S. premiere performances of Verdi’s Otello, with his brother later taking over the title role. In Milan, he was conductor for the premieres of Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur at the Teatro Lirico in 1902 and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly at La Scala in 1904. In 1909, he was appointed music director of the Chicago Grand Opera Company, the city’s first resident opera company.)

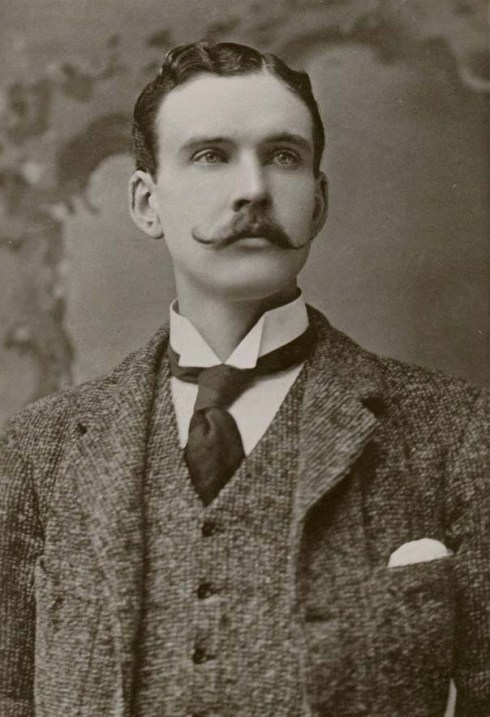

Campanini must have been under the weather during the run of Elijah in 1893. Charles A. Knorr (1852–1937) performed the tenor solos on March 13, and the Chicago Tribune review for the second performance reported “the indulgence of the audience was asked for Sig. Campanini. The music of the part of Obadiah he sang carefully and with fairly good success.”

The debut of Irish bass-baritone Plunket Greene (1865–1936), during this, his first tour of the United States, was one of the most anticipated events of the season. Singing the title role in these performances of Elijah, he possessed “rare qualities of a beautiful voice, artistic taste, thorough musicianship, and strong, emotional power . . . He is an artist in the best sense of the word, and his singing of the music of Elijah last night gave thorough, keen delight, and satisfaction. . . . Anything more beautiful in vocal finish or more touching in expressiveness than the latter noble air as sung by Mr. Greene has rarely been heard in this city.”

Greene continued to appear with the Orchestra, on subscription concerts at the Auditorium Theatre, at the World’s Columbian Exposition, and on tour at the Cincinnati May Festival. A close friend of Sir Edward Elgar, Greene was a soloist in the world premiere of The Dream of Gerontius in October 1900, was the dedicatee of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Songs of Travel, and in 1892 created the title role in the premiere of Sir Hubert Parry’s Job (later marrying the composer’s daughter). He authored Interpretation in Song, a valuable instruction book for singers; a biography of composer Charles Villiers Stanford; and Where the Bright Waters Meet, a testament to his love of fly fishing.

This article also appears here.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—according to Frederick Stock, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra‘s second music director, in Talks About Beethoven’s Symphonies—is “dedicated to all Mankind. Embracing all phases of human emotion, monumental in scope and outline, colossal in its intellectual grasp and emotional eloquence, the Ninth stands today as the greatest of all symphonies.”

Stock continues: “The Ninth is unquestionably the greatest of all symphonies not only because it is the final résumé of all of Beethoven’s achievements, colossal as they are even without the Ninth, but also because it voices the message of one who had risen beyond himself, beyond the world and the time in which he lived. The Ninth is Beethoven, the psychic and spiritual significance of his life.

“In the first movement we find the bitter struggle he waged against life’s adversities, his failing health, his deafness, his loneliness. The Scherzo depicts the quest for worldly joy; the third movement, melancholy reflection, longing—resignation. The last movement, the ‘Ode to Joy,’ is dedicated to all Mankind.”

“There’s something astonishing about a deaf composer choosing to open a symphony with music that reveals, like no other music before it, the very essence of sound emerging from silence,” writes CSOA scholar-in-residence and program annotator Phillip Huscher. “The famous pianissimo opening—sixteen measures with no secure sense of key or rhythm—does not so much depict the journey from darkness to light, or from chaos to order, as the birth of sound itself or the creation of a musical idea. It is as if the challenges of Beethoven’s daily existence—the struggle to compose music, his difficulty in communicating, the frustration of remembering what it was like to hear—have been made real in a single page of music.”

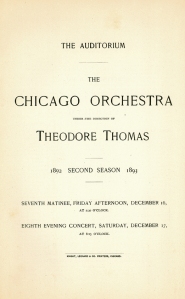

Founder and first music director Theodore Thomas first led the Chicago Orchestra in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on December 16 and 17, 1892, at the Auditorium Theatre. The soloists were Minnie Fish, Minna Brentano, Charles A. Knorr, and George E. Holmes, along with the Apollo Chorus (prepared by William L. Tomlins).

Sixth music director Fritz Reiner led the Orchestra’s first recording of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on May 1 and 2, 1961, in Orchestra Hall. Phyllis Curtin, Florence Kopleff, John McCollum, and Donald Gramm were the soloists, and the Chicago Symphony Chorus was prepared by Margaret Hillis. For RCA, Richard Mohr was the producer and Lewis Layton was the recording engineer.

Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus first recorded Beethoven’s nine symphonies between May 1972 and September 1974 for London Records. The recordings were ultimately released as a set (along with three overtures: Egmont, Coriolan, and Leonore no. 3); that set won the 1975 Grammy Award for Classical Album of the Year from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. The Ninth Symphony was recorded at the Krannert Center at the University of Illinois in Urbana on May 15 and 16, and June 26, 1972. Pilar Lorengar, Yvonne Minton, Stuart Burrows, and Martti Talvela were the soloists, and the Chicago Symphony Chorus was prepared by Margaret Hillis. David Harvey was the recording producer, and Gordon Parry, Kenneth Wilkinson, and Peter van Biene were the balance engineers.

Between September 1986 and January 1990, Solti and the Orchestra and Chorus recorded the complete Beethoven symphonies a second time, again for London Records; and again, the recordings were ultimately released as a set (along with two overtures: Egmont and Leonore no. 3). The Ninth Symphony was recorded in Medinah Temple on September 29 and 30, 1986. Michael Haas was the recording producer, John Pellowe the balance engineer, and Neil Hutchinson the tape editor. Jessye Norman, Reinhild Runkel, Robert Schunk, and Hans Sotin were soloists, and Margaret Hillis prepared the Chorus. The release won the 1987 Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.

On September 18, 20, 21, and 23, 2014, Riccardo Muti led the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in Orchestra Hall. Camilla Nylund, Ekaterina Gubanova, Matthew Polenzani (September 18), William Burden (September 20, 21, and 23), and Eric Owens were the soloists, and the Chorus was prepared by Duain Wolfe. The performance on September 18 was recorded for YouTube and is available in the link below.

This article also appears here.

During the Chicago Orchestra‘s second season, music director Theodore Thomas programmed Beethoven’s Symphony no. 9 for the first time with his new ensemble. The performances were given on December 16 and 17, 1892, at the Auditorium Theatre.

According to an account in the Chicago Daily Tribune on December 18: “Like whistling winds broken by the blare of trumpets and the crash of cymbals and again like a sigh breathed upon the strings of a harp, Beethoven’s ninth symphony and his music to Goethe’s Egmont were listened to by nearly 4,000 music-lovers at the Auditorium last night. . . . The highest social circles of the city were in attendance. Chicago’s cultured and fashionable classes enjoyed a musical festival in honor of the 122nd anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. For the first time in the history of the city the great composer’s birth was fittingly celebrated. In 1870 the 100th anniversary was observed with a concert in old Farwell Hall, but as compared with the event of last evening it was insignificant.”

What the reviewer recounted next is nothing short of jaw-dropping: “Mr. Thomas had his men play the last movement of the Symphony a full tone lower than it is written—a proceeding without precedent in the entire history of the great work and which bids fair to call down upon him the wrath of musical purists and classicists. The subject was vigorously discussed by musicians present at the concert last night, and, although many liberal minds defended the director in his action, conservatives who bitterly assailed him were not wanting. The men of the orchestra covered themselves with glory by playing the movement with entire accuracy a tone lower than was indicated by the notes on the music parts before them. . . .

“When the Apollo Club chorus of 200 voices [prepared by William L. Tomlins], together with Miss Minnie Fish and Mrs. Minna Brentano and Charles A. Knorr and George E. Holmes, joined with the orchestra . . . the majesty and grandeur of the music were highly appreciated and greeted with almost boundless applause. The words of the ‘Ode to Joy‘ were sung with such precision and distinctness they they could be heard and appreciated in every part of the house. When the notes of the Choral Finale had died away the vast audience applauded for several minutes.”

The reviewer described Thomas’s “innovation”—surprisingly, not mentioned at all in Adolph W. Dohn’s program note (the complete program book is here)—as follows: “The last movement of the Symphony Mr. Thomas gave in C minor instead of D minor, the key in which Beethoven wrote it. It was an act which demanded no slight courage on the part of the great leader, and there were not lacking last evening musical conservatives who indignantly accused him of ‘taking unwarrantable liberties with music’s masterpieces,’ and ‘marring the works of the great composers.’ Mr. Thomas did not make the change, however, save after long and serious consideration. To make the change meant to break one of the ironclad, time-honored rules governing symphonic form, and possibly to lessen slightly the brilliancy of certain passages. On the other hand, the change freed the sopranos from the necessity of singing numerous high Gs and As, and could but result in marked gain in the volume and quality of the tone produced. He weighed these matters and decided upon the transposition, a decision that liberal thinkers in the musical world will uphold him in and approve of.”

Even with the modification, the reviewer was moved to write: “The rendition accorded the Symphony last evening by Mr. Thomas and his forces was worthy of the work itself, of the master whose greatest power it represents, of the event the concert celebrated, and of the great leader to whom musical Chicago is indebted for so much. The orchestra was in its best condition, and upon it Mr. Thomas played as does a master upon some perfect instrument. The result was a performance technically flawless, interpretatively superb. . . . And last night the choral finale brought with it no disappointment. A larger chorus might have been wished for, perhaps, but in the Allegro energico and the great climax that follows, but in the other portions of the work—and it is in these that the chorus after all finds opportunity for effective singing, the voice parts in the climax being buried under a mountain of orchestral tone—in these portions, the 200 singers from the Apollo Club acquitted themselves most creditably, their work being satisfactory and deserving of sincere praise.”

There is no evidence to indicate that Thomas’s later performances of the Ninth Symphony were performed in a similar manner.

(The complete Chicago Daily Tribune article—courtesy of Proquest via the Chicago Public Library—is here.)

To open the 124th season in September, Riccardo Muti leads the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Chorus, and soloists in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The concerts currently are sold out, but check the website as last-minute tickets may become available.